Like Dr. Seuss.

I have been reading a history book, By the Bomb's Early Light, and while I am deeply grateful to Paul Boyer for putting such an impressive collection of material together, I've had a couple problems with his use of material. One is his assertion that a really questionable quote lifted from another source was "widely quoted" even though I cannot find the quote anywhere but his book and his source's book, but what really grated was this:

"Having for years been ignored, the issue of nuclear war suddenly seemed in danger of trivialization. Theodore Gesell ((wrong spelling of the last name is original to the text)) produced a Dr. Seuss book comparing the Cold War and the nuclear arms race to a quarrel over how bread should be buttered."

| |

| Silliest arms race ever? |

For those of you uninitiated, the story is basically the Yooks, who eat their bread butter side up, versus the Zooks, who eat their bread butter side down.

At first, the war starts with snitch-berry switches and slingshots. But then the leader of the Yooks assures a disheartened guard that those are old-fashioned, and the stakes are rising:

"All we need is some newfangled kind of gun.

My Boys in the Back Room have already begun

to think up a walloping whizz-zinger one!"

The "Boys in the Back Room" are portrayed as bespectacled, scientific types. They don't seem sinister, just... terribly eager. They're inventing and innovating, after all, for the good of the Yooks.

Geisel also addresses the way that popular culture plays a part:

"And our Butter-Up Band

marched up over the hill!

The Chief Yookeroo had sent them to meet me

along with the Right-Side-Up Song Girls to greet me.

They sang:

"Oh, be faithful!

Believe in thy butter!"

And they lifted my spirits right out of the gutter!"

|

| Butter propaganda! |

It becomes clear that the race is getting out of hand when the newest weapon comes with a description:

"This machine was so modern, so frightfully new,

no one knew quite exactly just what it would do! "

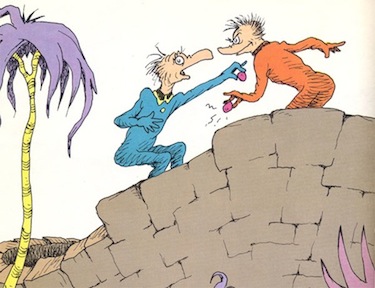

The part where the book starts to get downright chilling, however, is when the new general races to the office of the Chief Yookeroo, which is in a state of disarray. The Boys in the Back Room are clearly frazzled, and the Chief announces, while staying safely behind a wall and using a grabber of some kind to drop a device into the general's hands:

"THEY'VE INVENTED

THE BITSY

BIG-BOY BOOMEROO!

You just run to the Wall like a nice little man.

Drop this bomb on the Zooks just as fast as you can.

I have ordered all Yooks to stay safe underground

while the Bitsy Big-Boy Boomeroo is around."

Oh. My. Gosh. The man who taught me about counting fishes put the atomic bomb in fiction suitable for tiny children. That is huge. From the intentional similarity to the names of the earliest bombs, Fat Man and Little Boy, to the grim nod to the Yooks having to go into freaking fallout shelters, the reality of the situation is clear. Even kids who don't understand the context are getting the picture of how scary this thing is. The image of a line of grim-faced Yooks heading into an underground tunnel reading "Your Yookery" is not played for laughs. It's actually a pretty frightening image. It is also frightening as the focus goes back to the narrator, the grandchild of the guard/soldier/general, who notes:

Oh. My. Gosh. The man who taught me about counting fishes put the atomic bomb in fiction suitable for tiny children. That is huge. From the intentional similarity to the names of the earliest bombs, Fat Man and Little Boy, to the grim nod to the Yooks having to go into freaking fallout shelters, the reality of the situation is clear. Even kids who don't understand the context are getting the picture of how scary this thing is. The image of a line of grim-faced Yooks heading into an underground tunnel reading "Your Yookery" is not played for laughs. It's actually a pretty frightening image. It is also frightening as the focus goes back to the narrator, the grandchild of the guard/soldier/general, who notes:"That's when Grandfather found me!

He grabbed me. He said,

"You should be down that hole!

And you're up here instead!

But perhaps this is all for the better, somehow.

You will see me make history!

RIGHT HERE! AND RIGHT NOW!"

Grandpa leapt up that Wall with a lopulous leap

and he cleared his hoarse throat

with a bopulous beep.

He screamed, "Here's the end of that terrible town

full of Zooks who eat bread with the butter side down!"

Imagine you're a kid, identifying with this narrator. You're imagining your grandpa, a guy you probably look up to, go crazy like this, screaming about the destruction of an entire group of people. That's terrifying. And it's significant too, because it's showing how those we trust, and those who have been trying to do the right thing, can be pushed to these total extremes. It is not a story with a clearly painted bad guy. These characters are not engaging in mischief with unintended consequences like the Cat in the Hat. They know the stakes are high, but neither side can bring themselves to back down, and that's a pretty hefty concept to be bringing into a book for young readers.

Geisel does not pull his punch at the end, either. As the Zook general appears with his own bomb, there is a standoff at the top of the wall. The narrator, looking on, is clearly frightened:

"Grandpa!" I shouted. "Be careful! Oh, gee!

Who's going to drop it?

Will you... ? Or will he... ?

"Be patient," said Grandpa. "We'll see.

We will see . . . "

And that's it. The end. The Yooks and the Zooks do not see the folly of their violent actions, or the similarity of their cultures. They don't shake hands and agree it was silly to try to harm each other. They stand on the brink of mutually assure destruction, and the reader is left with the implicit question of whether the situation can ever be resolved.

And that's it. The end. The Yooks and the Zooks do not see the folly of their violent actions, or the similarity of their cultures. They don't shake hands and agree it was silly to try to harm each other. They stand on the brink of mutually assure destruction, and the reader is left with the implicit question of whether the situation can ever be resolved.The Cold War and the nuclear threat trivialized?

I don't think so, Boyer.

Wow, the little-known Seuss. I'm impressed. The uncharacteristic lack of resolution to the story is especially poignant.

ReplyDeleteI adore this post, Rowie. It makes the children's lit scholar in me want to sing. Children's literature has such potential for power... and, interestingly, adults' dismissal of it also gives it a great deal of room for *subversive* power. "Who cares what the book says? It's only a children's book."

ReplyDeleteDude, mind blown. Never made the connection either. Amazing!

ReplyDeleteTo quote Dr. Seuss himself.....

ReplyDelete"Those who mind don't matter,

and those who matter don't mind."

~ Dr. Seuss

{visit my blog >> http://GoodLifeFilm.blogspot.com <<}